"I Can't Draw Noses!"

Yes you can.

🌟Hey! I’m including an AUDIO file of this edition (scroll to the very bottom). Normally, these are only for paying subscribers. If you like the convenience of being able to listen to The Accidental Expert while you’re making breakfast, jogging, or hiding in the storeroom from your boss, then please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thanks!🌟

Last time, I wrote about the two kinds of students I have encountered who are least likely to advance in their art studies or careers. And some of your comments confirmed that the mindsets of these students were harmful in fields outside of art.

I also mentioned a third kind of student (the most common, in my experience), who wants to improve but feels stuck. Perhaps this is you?

You might recall that I promised I would share the simple method I use to help such students move past this block and make real progress. I have found it to be most successful.

Here it is: be specific.

That’s it. It’s a simple idea, but very powerful.

Let me explain.

About ten years ago, in a portraiture class I was teaching, a flustered student said to me, “I can’t draw noses.”

“That’s a lie,” I replied.

“Seriously, I can’t,” she insisted. “I can draw eyes okay, but I always mess up noses.”

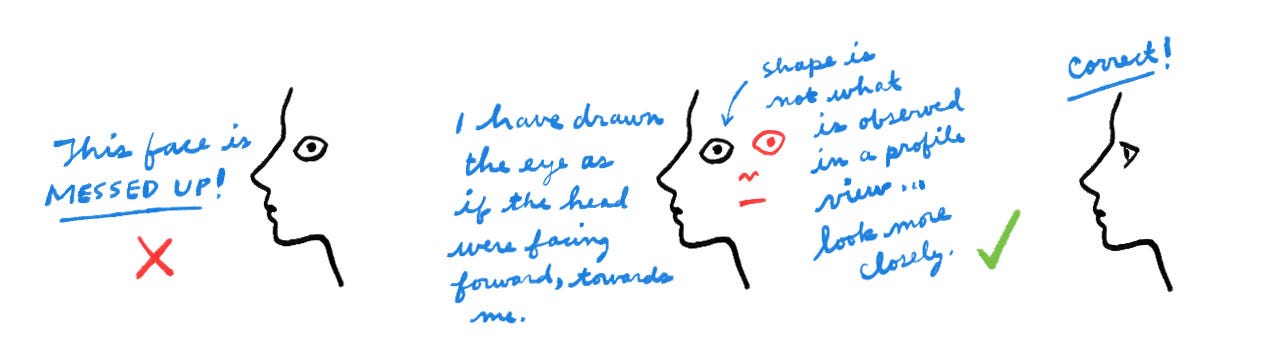

I went on to explain that if she could draw eyes, she could draw noses — (if you can draw an eye, you can draw an elephant, a Volkswagen, or a nose*) — but the real problem was the language she was using in her statement: she was not being specific. As a result, she had inadvertently put herself in a corner, psychologically.

“I am being specific! I said I can’t draw NOSES.” She insisted.

I told her this kind of specificity was not what I meant and then went on to clarify:

“Look at the nose you have drawn and now look at the model. Is the model’s nose longer or shorter than what you have on your page, relative to the other facial features? It’s shorter. You can measure and prove this easily. Is the bridge of the nose on the model actually visible as a ‘line’ on the face from this angle, or is there barely any indication of it, other than a subtle shift in value? You have drawn a strong line that isn’t there. Can you see the nostrils or are they obscured by the form shadow of the underside of the nose? Draw the shape of the shadow and don’t worry about the nostrils— they are too difficult to see and are a distraction.”

There is nothing more satisfying to a teacher than seeing a light bulb moment as it happens. This was such a moment.

Using specific language to identify what is wrong with our work gets us quickly to a fix. This practice, if truly internalized, not only gives us a consistently reliable method to improve, but a boost of confidence, as well. Knowing precisely what needs to be corrected gets you more than halfway to the solution.

To make progress in our creative practices with greater speed, we need to adopt the same approach as medical doctors. Diagnose the problem, working from the general down to the specific. Then, prescribe the remedy.

Instead of saying this: That shoulder is off.

Say this: That shoulder is drawn too far to the right. It should be moved so that it aligns vertically just about halfway between the forearm and wrist.

In the example above, the clear description of why the shoulder is ‘off’ gives the artist an immediate plan of action to make a correction and then continue to progress through the drawing.

And while it is certainly easier for artists with more experience to quickly identify the problems in their work, we are all capable of doing more of this at any stage in our development. We just need to stop, take a breath, observe carefully and then only use words that mean something. And besides, telling ourselves things like “I can’t draw noses,” or “My painting is all wrong,” does us absolutely no favors. It’s not at all constructive and has no place in our learning process.

Hey - good news! This approach applies to pretty much any skill you learn.

For example, Writing:

My stories are boring.

No!

I have noticed that the authors I admire use more descriptive language only when it is necessary for the reader to understand something more clearly (a place, a personality) and only when these descriptions do not upset the pacing. I have been describing every person, place and moment in excessive detail and it not only gives my writing a repetitive feeling, but it does not allow me to speed things up or slow them down as my plot requires.

Yes!

Or Music:

This piece I’m playing on the violin doesn’t sound as cool as the recording I heard.

No!

In the recording I heard, the musician really emphasized the dynamics in their playing of the piece; this range of volumes and intensity made everything more exciting. And they used more vibrato. I can try doing this!

Yes!

So there you go. It seems simple, but most of us need to retrain ourselves to change the language we use when we talk about what’s lacking in our own work. Specificity is the key to success. Be objective, be honest, and use words that describe your work accurately. Avoid these words: good, bad, boring, dull. Get past these and move on to the good stuff: louder, softer, longer, shorter, darker, brighter, more acute, more obtuse, straighter, rounder, bolder, closer, farther, faster, more, less, tighter, looser, above, below, sharper, hazier, saturated, desaturated, detailed, open, textured, cooler, warmer …

Want to level up from there? Be even more specific.

Instead of saying, More to the right, say, 2 centimeters to the right.

But hey, don’t get too crazy. A little goes a long way. 🙂

*Sorry to ruin the romantic notion that art is all about natural talent, but drawing is, at its core, learning to see more carefully and with an eye for relationships between the parts, big and small, of whatever you observe. See a shape or a color, put it on the paper. Repeat. Bonus: after drawing specific things a handful of times, you build up a visual vocabulary and you can refer to it as needed.

This particular edition of The Accidental Expert could, I believe, help a lot of students, and not just those studying art. It’s easy to get in the habit of using negative non-constructive language when we are wrestling with problems in our work, but it gets us nowhere. The specific language examples shared in this piece can make a real difference not just in how people learn, but in how they treat themselves when they are frustrated with stagnation or uncertainty on the journey towards mastering a skill. So, please share this one far and wide! Thank you.

🌟You can listen to this edition of The Accidental Expert! Audio versions are normally a perk for paid subscribers, so if you want more of these, please consider becoming one for just $3/month! Thanks, and enjoy.

I’d love to hear what you think about this approach to learning. It has worked for me as both a student and a teacher.

Okay, until next time, take care of yourselves and each other, remember to be kind, and I’ll say, Ciao for now.

❤️Support me here: Digital art products, my book, my meditative drawing app

From a fellow art teacher--thank you for sharing this perspective! I will be incorporating it into my lesson this week!

Excellent! Just plain excellent!!